By Jan Boukal

The word “šlechta” – Czech for aristocracy or nobility – is based on the old German “slahta” or “slahte”, meaning a house, strain or origin. The origins of the aristocracy in the Lands of the Bohemian Crown date back to the early middle ages. We will probably not be entirely wrong stating that our aristocracy developed from the fighters for counts and kings who put the soldiers in charge of some of their property. Often this property was taken over by the soldiers who later considered it their own. The heritability of the property in the hands of the aristocrats was sanctioned by the codex Iura Conradi in 1189. In the times of Charles IV, a nobleman had to prove his aristocratic origin and be a free holder of a property that was subject to the land law. The aristocratic origin was mainly proven by a visible sign inherited from the ancestors – a coat of arms (Czech: erb, from the German verb erben = to inherit). Aristocratic coats of arms could be seen on seals, shields, standards, or architectural decorations of aristocratic manors and church buildings.

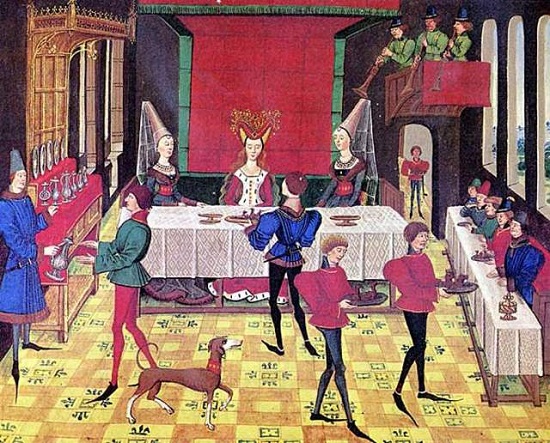

Aristocratic feast

We may assume that the aristocracy made about 2 % of Bohemian and Moravian population in the 14th century. The historians still use a bit ahistoric and confusing terms upper and lower nobility, while the contemporary terminology recognizes several categories: feudal lords, yeomen, thanes, knights and squires. The most important feudal houses of the Luxembourgian era include the lords of Rožmberk (Rosenberg), Wartenberg, Rýzmburk (Riesenburg), Svamberk, Šternberk (Sternberg) or Dubá. The members of the feudal houses were in charge of important offices, frequently present at the royal castle. In Prague, they bought or built spectacular houses to stay while in office. During Charles’s era, the lords had their majestic castles built, such as Maidstein (Dívčí Kámen), Helfenburg near Bavorov, or Kost; these castles were not only their places of residence and economic centers of their domains but also fortresses and symbols of their power over the surrounding land. Nearby a residential castle, a town could have been built. The lords were often also donors of monasteries and churches that in turn became their house necropolises and, through signs and depicted coat of arms, also house memorials.

During the reign of Charles IV, and decades later, the most powerful feudal house in Bohemia was the house of Rožmberk (Rosenberg). They rose to power in the early 14th century, having inherited considerable fortune from the deceased relatives – Lords of Krumlau. Peter I of Rosenberg married Viola of Teschen, the widow of the king Wenceslas III. The marriage was facilitated by king John of Luxembourg, to win the favor of the mighty nobleman. Peter’s sons were given important offices in the court of Charles IV, but they also had endless disputes with the king, struggling to strengthen their power and domain as much as possible. In the 14th century, the Rosenbergs expanded outside their traditional territory in the Southern Bohemia, and acquired numerous estates in the western and central part of the land. Their property in the period is documented in the “Rosenberg Urbar”, the oldest aristocratic urbar in our country.

Peter I of Rosenberg

Compared to the feudal estates, the property of most knights and yeomen was small, and their political power was close to zero in the 14th century. For example, they could only own a single village with a modest fort. Many representatives of these groups lost their property for various reasons (inheritance problems, debts etc.), so they had to seek help from more powerful lords, offering their services as caretakers, members of castle military staff etc. A considerable number of destitute aristocrats turned criminals to avoid poverty.

As this brief paper indicates, the aristocracy consisted of very different classes, in terms of both property and social status. While the lords participated in the government alongside the king, knights and yeomen were also considered aristocratic residents in the kingdom, but many of them – mainly ambitious and capable individuals – weren’t really satisfied with their social and material situation. All this was to change soon after Charles’s death. His son Wenceslas didn’t trust the lords much as they had betrayed him several times, so he sought company of poorer aristocrats, and some of them took this opportunity to start a stellar career in his service.

Bibliography:

BOBKOVÁ, Lenka – BARTLOVÁ, Milena. Velké dějiny zemí koruny české IVb. Praha-Litomyšl: Paseka, 2003.

MACEK, Josef. Česká středověká šlechta. Praha: Argo, 1997.

ŠIMŮNEK, Robert. Reprezentace české středověké šlechty. Praha: Argo, 2013.