By Jan Tomášek

In 1313, Baldwin returned to his archdiocese he had left three years before to accompany his older brothers on their quest for the imperial crown. The Roman journey, also co-funded by Baldwin, was a key event in the life of the archbishop, then 28 years old. He lost both brothers and the sister-in-law in Italy, which made him head of the Luxembourg house. All the hopes of the house now depended on him and his 17 years old nephew John, the King of Bohemia since 1310, whom Baldwin began to support. John cooperated with his uncle until the last years of his life when he was overshadowed by his own son, who suited Baldwin’s nature better. Until 1316, Baldwin helped his nephew manage his Luxembourg estates, as the latter was busy in Bohemia.

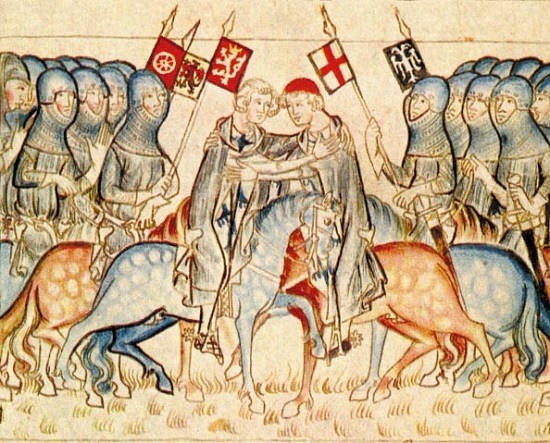

Baldwin meeting with his nephew, Bohemian King John of Luxembourg (Codex Balduini Trevirensis)

Due to the votes of Trier and Bohemian electors, the influence of the Luxembourg house on the election of the new Roman monarch was rather big. The last election of the Luxembourgian Earl Henry had taken place only six years ago, and the new fight for the Roman throne broke out, attended also by Baldwin of Luxembourg and his nephew John. There were two favorites in the contest for the Roman throne this time – the first was John of Luxembourg (aka John of Bohemia), supported not only by his uncle but also by the Mainz archbishop Peter of Aspelt, the former chancellor of Wenceslas II; the second was Frederick of Habsburg, aka Frederick the Fair. Both pretenders were sons of former Roman kings. However, the Luxembourg house wasn’t lucky in the half of 1314. Frederick of Habsburg gained the support of the Cologne archbishop Henry II, Rudolph of Bavaria and Henry of Carinthia, still using the vacant title of the King of Bohemia. Under these circumstances, John’s position was too risky, and Peter of Aspelt withdrew his support. Together with Baldwin, they started negotiations with Louis of Bavaria of the Wittelsbach house in September 1314, and after some consideration, Louis agreed to contest. The vote was less than a month away, and the conflict between Louis and Frederick of Habsburg seemed inevitable.

The Luxembourgian representatives kept supporting Louis and finally their candidate won. In the late September, Louis of Bavaria issued numerous documents promising various gifts to the archiepiscopates of Mainz and Trier, and also to John of Luxembourg who, upon the agreement with his uncle, also supported the candidate from the Wittelsbach house. Louis gave John ten thousand talents, insured by the mortgage of Cheb region and the castles of Floss and Parkstein in upper Bavaria. Later in 1322, after Louis’s final victory, John obtained the Cheb region for good. He remained true to the Wittelsbach monarch in the later years, even though it led to problems in relationships with the papal office.

In the early 1320s, Baldwin saw new opportunities to strengthen his power. In 1320, the Mainz archbishop Peter of Aspelt died, and the Mainz chapter elected Baldwin of Luxembourg the new archbishop, against the will of the pope (who sided with the Habsburg in the ongoing dispute over the imperial throne). However, Baldwin never became the archbishop; he decided to keep his influence in the Mainz archdiocese by becoming its administrator, and remained in this position, with some breaks, until 1336. Just like in Mainz, he became the administrator of Worms and Speyer episcopates (probably in 1331), and used this position to mediate the disputes with the papal court.

Views Baldwin of Luxembourg from Carthusian monastery in Trier (author: Markus Groß-Morgen)

During these years, Baldwin could pay full attention to the issues in his archdiocese. These are also the years of some of his famous foundation work. He was very fond of the Carthusian order, for which he founded convents in Trier and Koblenz. He even kept his own special cell in the Trier convent to meditate. He clearly favored both these towns and initiated, for example, the reconstruction of the Trier stone bridge and the building of a similar bridge in Koblenz, still bearing Baldwin’s name to this day. Even larger project involved the completion of gothic eastern towers of the Trier cathedral.

The difficult relationships between the Emperor Louis of Bavaria and the Pope John XXII brought Baldwin back to the top level of the imperial politics in late 1330s. The pope tried to get Baldwin on his side, so he made several promises in favor of the archbishop’s nephew John. One of the most important Luxembourgian successes at the papal court involved the promotion of the Prague episcopate in 1344. Baldwin never really gave up on Louis of Bavaria, but he started planning the candidacy of his grand nephew Charles with John of Luxembourg.

In 1345, young Charles promised to follow Baldwin’s advice and refund all his costs for election and coronation, up to 6,000 talents. A year later, Baldwin required another confirmation of his rights, and Charles obliged on May 22, 1346. The agreement primarily involved the confirmation of privileges of the Trier archiepiscopate, full refund of all costs related to the election, and promise of friendship with the Trier archiepiscopate in case Charles would become the Luxembourgian earl. This is another proof of Baldwin’s foresight. Of course he kept the wealth of his house in mind, but on the other hand he cared for his archdiocese, the situation of which also depended on the relationships with neighboring Luxembourgian earls. And we can clearly see that pragmatic Charles suited Baldwin better than John, in terms of the political style. Though John was of similar age as Baldwin, he probably objected to the agreement, and refused to add his seal. Baldwin however considered the agreement sufficient, and sent a letter to Louis on May 24, officially withdrawing his support.

Bridge in Koblenz, built by Baldwin of Luxembourg (author: Holger Weinandt)

Charles’s ascent to the imperial throne and the tragic death of Louis of Bavaria marked another Baldwin’s diplomatic success. Though Charles was crowned the Roman king in Bonn in November 1346, the coronation in Aachen, traditional coronation town of Roman royals, could only take place once the conciliation with Louis’s heirs had been achieved. In May 1349, Charles completed his victory by the coronation in Aachen, where the Cologne archbishop Walram, seriously ill, was replaced by Baldwin of Luxembourg. In September 1346, the new Roman king confirmed the payment of his granduncle’s costs, which reached 250,000 florins by 1349 (about 885 kg of gold), and granted him the domains Echternach, Bitburg, Remich and Grevenmacher with all income they generated. The uncle-nephew relationships were correct until Baldwin’s death in 1354.

When Baldwin of Luxembourg died, the Luxembourg house lost an outstanding diplomat and one of the most influential men in the empire. He witnessed the rapid growth of his family and then the long struggle to keep the achieved position. He outlasted all his brothers, affected the election of three Roman kings, laid the foundation of centralized Trier Electorate, and, above all, managed all the time to keep the balance between his personal ambitions, family interests, and well-being of his archdiocese. His importance is indicated by his noble grave, finished around 1362 in French style in the western part of the Trier cathedral.

Bibliography:

HEYEN, Franz-Josef (ed.). Balduin von Luxemburg: Erzbischof von Trier – Kurfürst des Reiches 1285–1354. Mainz: Verlag der Gesellschaft für Mittelrheinische Kirchengeschichte, 1985.

HOENSCH, Jörg Konrad. Lucemburkové: pozdně středověká dynastie celoevropského významu 1308–1437. Praha: Argo, 2003.

MARQUE, Michel – PAULY, Michel – SCHMID, Wolfgang, a kol. Der Weg zur Kaiserkrone: der Romzug Heinrichs VII. in der Darstellung Erzbischof Balduins von Trier. Trier: Kilomedia, 2009.

SPĚVÁČEK, Jiří. Jan Lucemburský a jeho doba. Praha: Svoboda, 1994.

Project manager

PhDr. Daniela Břízová

Charles University in Prague

Ovocný trh 3-5

Prague 1

116 36

Czech Republic

tel: +420 224 491 851

tel: +420 702 124 672